Ifugao Rice Rituals

The cultivation of the tinawon, the local rice variety, is anchored to elaborate rituals, in each phase of the agricultural cycle. Epics, myths, ballads, and prayer chants accompany each activity in the rice fields. This intangible heritage provides a deeper understanding of Ifugao history, religion, spirituality, and culture.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

The rice rituals performed by the Ifugao are numerous and elaborate: There are at least seventeen rice rituals throughout eleven of the twelve months (from October to August) of the Gregorian calendar (Barton 1946: 110-126; Hamilton 2003: 453-454). Barton (1946: 109-126) lists fifteen agricultural rites in an annual calendar. Most of the agricultural rites, including seeding, weeding, transplanting, and bringing rice to the granary are performed in the family circle by mumbaki, or males who are specially trained for rituals. Only a portion of the rice harvest rituals are performed by the larger village community.

The Ifugao observe elaborate ritual offerings for every single phase of the rice cycle from the sowing of consecrated seeds meticulously selected by highly skilled elderly women, to the harvesting of the ripened grains. The rice rituals follow the natural cycle of the tinawon, or the heirloom rice varieties that have been handed down by gods of the Skyworld according to Ifugao oral histories.

These agricultural rituals are sponsored by the tumonak, the agricultural leaders whose landholdings may not be the widest in the area, but which are consecrated by deities to be the ritual field for a particular agricultural district (boble). The tumonaks are necessarily of the kadangyan class, families or individuals who perform lavish prestige rites to earn a place among the elite of Ifugao society. There is usually one tumonak in every district who may be a man or a woman but with one or two alternates who would take his or her place in case s/he fails in her/his duties. The most important role of the tumonak is to maintain the synchronicity of labor carried out in the rice terraces and at the same time maintain the rice rituals. Unfortunately, we now speak of the tumonak more as an institution of dwindling culture as this “keeper of rituals” is doomed to fade away along with the old ways as the new religion incessantly wreaks havoc at the very core of the old religion. Currently, only two tumonak in the agricultural districts of in Hungduan and Batad still maintain their authority as rice ritual leaders.

Most are performed in the rice granary or in the house of the sponsoring couple. Sacrifices of chickens, pigs and rice wine plus the usual areca nuts and betel leaves are given to the Ifugao gods to ask for protection from pests, rice diseases and for the general welfare of the village. In their order of performance within the agricultural year, the following are the rice rituals:

- Bringing out of the first rice bundles from the last harvest (Lukya)

- Sowing of rice seeds (Panal/hopnak)

- Transplanting of rice seedlings (Bolnat/Pingil)

- Feast after the transplanting of seedlings (Kulpi)

- Ritual when rice plants grow new leaves (Hagophop)

- Ritual for protection of rice from pests (Tagtag/dog-al)

- Ritual when rice plants form grains (Paad)

- Harvest ritual (Kolating/Ahi-ani/Bfoto)

- Post-harvest general welfare rite for villagers asking the gods for protection from ailments and for prosperity and peace (Upin)

- Ritual for the lifting of prohibited food and gathering of certain vegetables, fish and other aquatic food from the rice fields imposed during the harvest season (Kahiw)

- Thanksgiving ritual for the year’s harvest (Bakle)

There can be slight variations in the rituals performed in the different regions of Ifugao but the purpose remains constant. Among the Hapao people, the end of the agricultural cycle is marked by the punnuk sponsored by the tumonak (otherwise called as dumupag in the Hapao area). For instance, when the rice terraces turn from green to yellow, the ripened rice grains are harvested, and then a ritual is performed to mark the end of the harvest season. The punnuk, a post-harvest ritual is performed by the residents in the villages of Hapao, Baang and Nungulunan in Hungduan, Ifugao.

Click here to add your own text

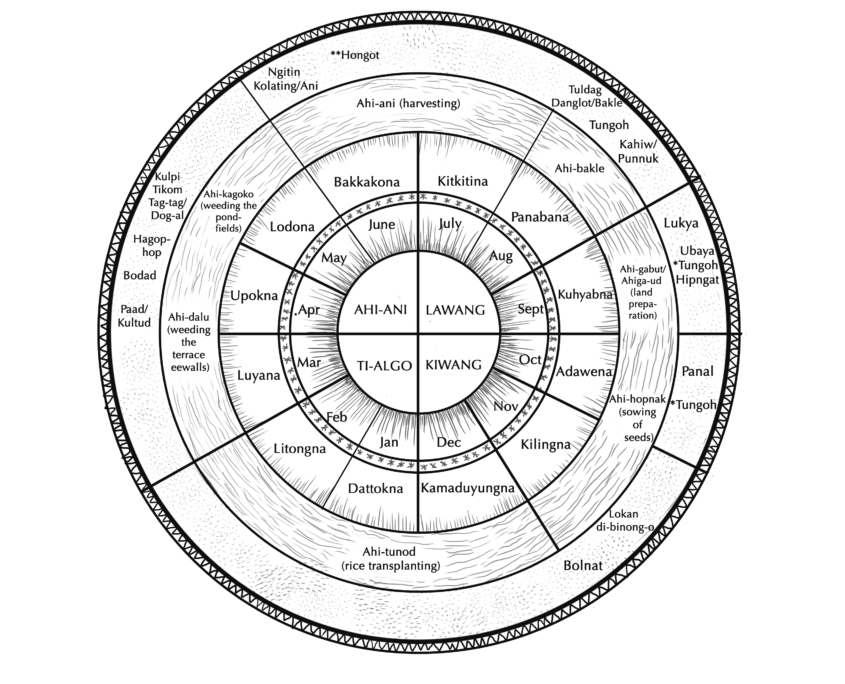

The Ifugao agricultural calendar has been adjusted to correspond to the Gregorian calendar, and specific rituals complement particular rice-farming activities. The inner circle represents the four seasons of the Ifugao agricultural calendar: Lawang: season of plenty (marriages and prestige rites are conducted during this period); Kiwang: planting season (rainy season); Ti-algo: season of the sun (“hungry time,” since it is the growing period of rice); Ahi-ani: harvest season (the most sacred, a period of fasting and abstinence from vegetables and anything obtained from water). The third spoke from the center represents the Gregorian calendar, while the fourth spoke represents the Ifugao months. The fifth outer spoke shows labor stages associated with wet-rice production. The outermost circle provides a list of rituals associated with each stage of wet-rice production. In the order of performance within the agricultural year, the following are the rice rituals of the Ifugao: (1) bringing out of the first rice bundles from the previous harvest (Lukya); (2) Kadangyan welfare ritual (Ubaya); (3) ritual to appease spirits as stored seeds are laid in seedbeds (Lokan di binong-o); (4) ritual for sowing of rice seeds (Panal); (5) transplanting of rice seedlings (Bolnat); (6) Paad is done when rice grains are about to mature: ritual that binds the Ifugao to a promise of abstaining from eating legumes, fish, and other aquatic food until the performance of the Kahiw ritual (Paad); (7) ritual to petition the gods to make the plants bear abundantly (Bodad); (8) ritual to ask the gods to make the rice grow abundant (after the kulpi and to open the weeding season): riceponds are rid of grass and other aquatic plants, and dead or stunted rice plants are removed and replaced (Hagophop); (9) Ritual for protection of rice from pests (Tagtag/ Dog-al); (10) ritual to protect rice from destructive birds and insects (Tikom); (11) feast after thetransplanting of seedlings (Kulpi); (12) ritual offered to the covetous gods done on the eve of the harvest day to ask this group of gods not to covet the rice harvest (Ngili); (13) harvest ritual (Kolating/Ani); (14) ritual related to the filling of the granary with rice bundles (Tuldag); (15) thanksgiving ritual for the year’s harvest (Danglot/Bakle); and (16) ritual for the lifting of prohibited food and the gathering of certain vegetables, fish, and other aquatic food from the rice fields imposed during the harvest season (Kahiw/Punnuk). Tungoh is a ceremonial field holiday where no one is allowed to work in the fields (ceremonial idleness); Hongot is a ritual conducted simultaneous with the kolating if the rice field is to be passed on to a newly married child of the sponsoring couple