Ifugao Inabol

Traditionally, the Ifugao people weaved these blankets for funeral or ritual purposes, legal proceedings, and to represent one’s social class. It is made in a series of six steps that includes a ritual consisting of chanting, storytelling, or sacrificing, and then a combination of winding, dyeing, and weaving.

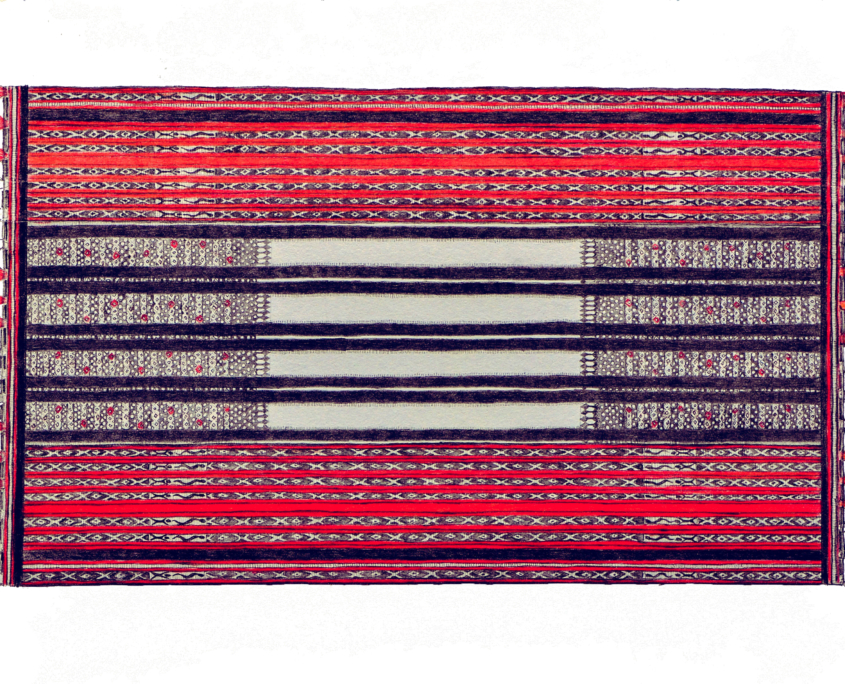

Pictured above: The Pinagpagan (or Dilli)

The pinagpagan is often misunderstood as exclusively for burial purposes. On the contrary, the pinagpagan is also used as a ceremonial blanket for kadangyan mumbagols, mumbaki of high ceremonies. Elderly kadangyans are also entitled to wear the pinagpagan in lieu of the bayaung.

The “pagpag” design of the pinagpagan is composed of the binongogan and the hinulgi patterns. This pair of pagpag patterns woven in odd numbers from 5 up to 15 (in the Kiangan area) is what is counted by the elders when determining the proper blanket for a deceased Ifugao kadangyan. The number of pagpags originally indicated the number of days of a kadangyan’s funeral. The term pagpag conveys the idea of what has been repeatedly beaten with a stick particularly the huklit or the finishing gape rod.

The Ifugao take on an important, lengthy process to what they call their Binobodan weaves. The process includes six special steps into producing a weave that holds its own meaning with every different color and technique, all while strengthening their connection to higher gods. Through a ritual that starts with chanting, sacrificing chickens, and the reiteration of stories about weaving, and ends with butchering a pig, this brings the blessing of the cotton thread and the physical wellbeing of the person weaving. After these rituals, the weaver is allowed to proceed onto the actual procedure: munpudun (winding), munha’ud (warping), munbobod (tying), muntayyum (dyeing), munha’ud (re-warping), and mun-abol (weaving). It is essential to the weaver and the Binobodan weave that the thread spacing and count variations are correct.

The various designs of the traditional Ifugao blanket represent social hierarchy and status. Furthermore, they play an important role in funerals, rituals, and legal activities. The more intricate the design, the more prestigious the wearer was in society. The most intricate design, Kinuttiyan, was used by the highest levels of nobility, known as the kadangyan, for both funerals and rituals. The design of the Kinuttiyan differs drastically from that of the Kintog, which is plain and used by the lowest class. Each symbol on the blanket may represent an important facet of the ritual or funeral process, such as the messenger deity between the gods and Ifugao people, or the ancestral spirits who have achieved demigod status in the afterlife. In addition to rituals and funerals, gifting the blankets could also serve legal purposes, such as the recognition of illegitimate children.

The practice of Ifugao weaving is maintained today due to the initiative of the Indigenous Peoples Education (IPED) Center. This center established the Kiyyangan Weavers Association (KIWA), where KIWA members take on a new apprentice every year and pass down this traditional practice to future generations. This organization began with 15 elderly weavers, and tripled their membership within four years! With the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic, KIWA members provided woven masks to their community at no cost. This generous act supported especially farmers who could not afford masks yet needed to wear them to sell their crop at the public market. Over quarantine, the textiles Ifugao weavers produced became more popular, increasing the demand for their threads. Although weavers still pass down traditional Ifugao patterns, they have the liberty to find contemporary works online and weave these less intricate designs as well. Whilst upholding tradition and meaning behind the practice of weaving, the Ifugao people continue to innovate their craft with current events.